A new movie is bringing attention to a painting that some consider to be the Austrian "Mona Lisa" — while others argue it’s just a society portrait, and not a great one at that.

The painting is Gustav Klimt's first portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer. As re-told in the film "Woman in Gold," Viennese émigré Maria Altmann sued the Austrian government in 2000 to recover family artworks seized by the Nazis. Among them was Klimt's famous portrait of her aunt: a dark-haired woman, sitting on a chair, covered in golden ornamentation.

The film centers on Altmann's six-year battle, which she won, and stars Helen Mirren as Altmann and Ryan Reynolds as her lawyer Randol Schoenberg.

The movie ends before the painting comes to New York City. But in 2006, the Altmann family sold the "Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I" for $135 million to cosmetics heir Ronald Lauder, who founded Neue Galerie. It was the highest price ever paid for a painting at the time.

In conjunction with the movie, Neue is presenting an exhibit looking at the history of the painting. During the press preview last week, Lauder said he is very proud of the piece. “This is the best picture we have and frankly, there is nothing else like this. Even 'The Kiss' in Austria, I think, is not as good as this,” he said.

But in this interview, WNYC’s art critic Deborah Solomon disagreed. “I think it’s pretty overrated as a painting. It is a society portrait and to me it has none of the adventurous spirit of other works of that era,” she said.

Examples from the same year, 1907, include Pablo Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d'Avignon,” and Henri Matisse’s “Blue Nude,” Solomon said. “Those were paintings that would change the history of art and smash up the single-point perspective that have prevailed in art since the Renaissance.” For her, the portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer doesn’t measure up. “For me, it feels like a trophy,” she said.

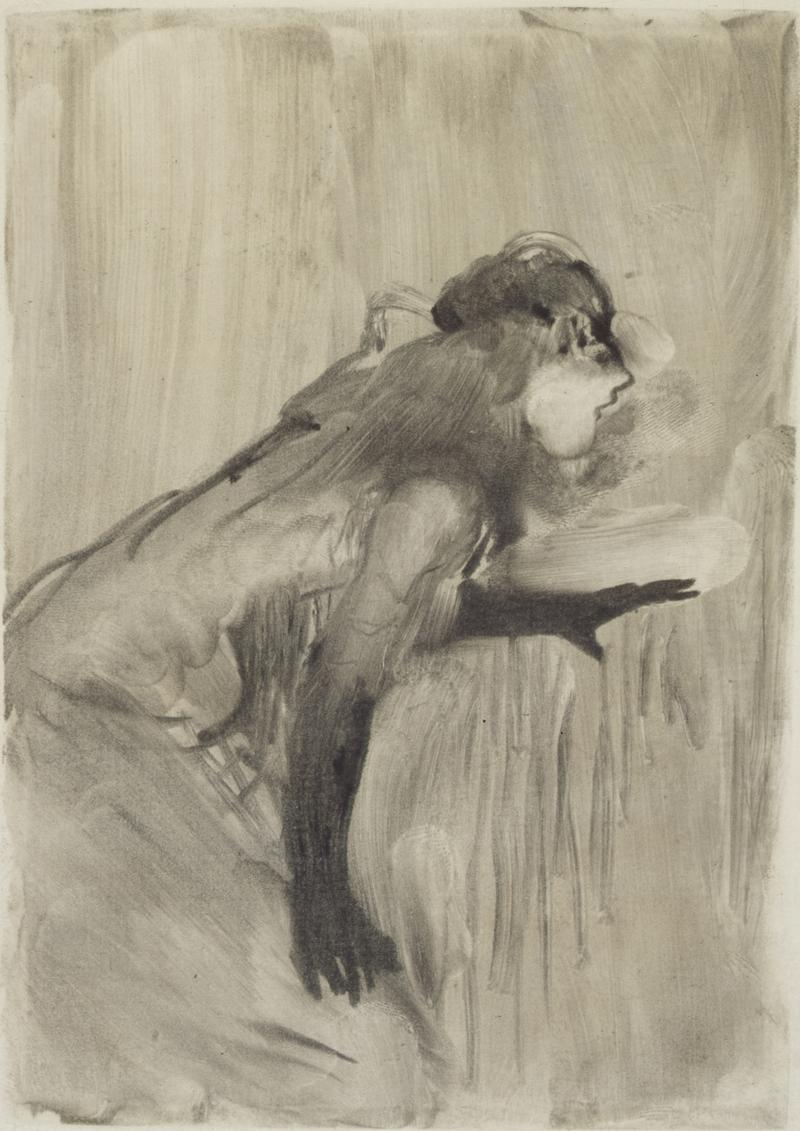

The exhibit at Neue Galerie features the painting and about 50 other works, including vintage photographs, jewelry and several sketches – it took Klimt four years to complete the piece. “Gustav Klimt was one of the greatest draftsmen of all time, and as you go through the small show, but a very interesting one, you see that he drew hundreds of sketches for the painting,” said Solomon.

What do you think of the painting Adele Bloch-Bauer I? Do you think it's the Austrian "Mona Lisa," or do you agree with Solomon that it's overrated? Join the conversation with a comment.

Neue Gallerie founder Ronald Lauder, who bought this painting for $135 million, says it’s the best in the museum’s collection. But WNYC's art critic says it's pretty underwhelming.