In the 1990s, “identity art” was a maligning phrase among mainstream critics. It referred to art that emphasized racial or sexual indignity at the expense of aesthetic content. Such art sprang from “the culture of complaint,” to borrow a book title from Robert Hughes, the celebrated art critic of Time magazine. He didn’t believe that artists consumed by a sense of social grievance could do justice to the Big Issues of Art.

I thought of that book, and how wrong Hughes was, as I made my way through “Kerry James Marshall: Mastry,” a magnificent and surprisingly entertaining retrospective of 70-plus paintings now on view at Met Breuer annex of the Metropolitan Museum. It’s certainly one of the top two or three best museum shows in New York right now, and it abounds with pleasures. Here is an artist who can tackle the history of racial abasement while somehow making room to cleverly muse on Manet, Fragonard, Mondrian and the flying bluebirds in Hallmark greeting cards – in short, the history of art and image-making.

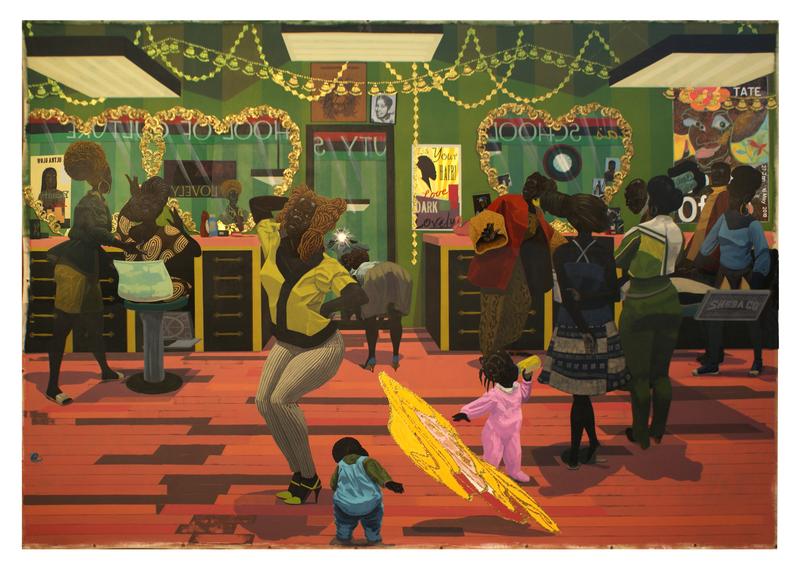

True, Marshall, an African-American painter of 61, based in Chicago, puts the theme of racial injustice at the center of his work. He speaks of his paintings as a conscious attempt to repair historical wrongs and insert black figures into the lily-white story of art. On one level, he’s a genre painter who favors glimpses of everyday life. He paints scenes in which African-American men and women might meet for a drink, go to the barber for a haircut, or attend a barbecue on July 4th. The figures tend to have the same coal-black skin. They function more as symbols than as individuals; they’re the spawn of Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man” and a society bent on racial profiling.

Nonetheless, the true subject of Marshall’s work is probably his love-hate relationship with the art of the past, especially American abstract art. As much as he may admire Jackson Pollock’s drip paintings or Willem de Kooning’s peachy-cream brushstrokes (look for references to them throughout the show), he is constantly asking whether an artist can be morally justified in embracing abstraction if it means ignoring social ills. Born in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1955, the son of a postal worker, Marshall was still in grade school when his family moved to Los Angeles, in time to witness the Watts riots that became an international symbol of America’s racial torments.

Met curator Ian Alteveer has done an inspired job with the exhibition, spreading it out over two spacious floors of the Met Breuer. It fills the third floor and fourth floor with a natural sense of proportion. You cannot ask for a more prestigious space in which to celebrate the art of this country, and the Met is to be congratulated for doing the show in an appropriately grand and “mastry” way.